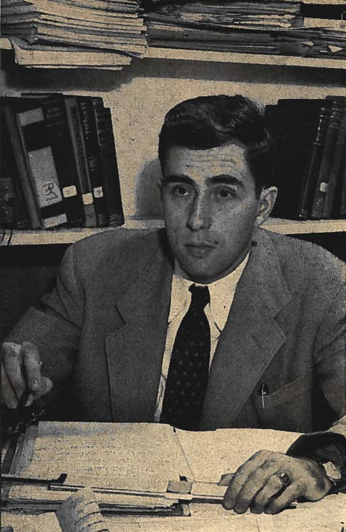

Dr. Gerald Bull graduated from UTIA in 1951. He was 23 years old and had completed both his MASc and his PhD in 3 years. So, it is little wonder that when Maclean’s Magazine published an article about Bull on March 1, 1953, they titled it “Jerry Bull Boy Rocket Scientist”, and described him as looking “almost as young as... an embryo space cadet.”

Thirty-seven years later, on March 22, 1990, Bull was launched into international notoriety when he was assassinated outside his apartment in Brussels, Belgium. At the time, Bull was engaged in ballistics work for Saddam Hussein. Much has been documented about Bull, including at least four books, numerous documentaries, an HBO movie called Doomsday Gun, and endless Google pages of articles that include everything from publications like the New York Times and the Washington Post to conspiracy theory threads. There are even Gerald Bull hashtags on Instagram and Twitter(X), evidence that there is still interest in the notorious Bull to this day.

What is not covered extensively is the role that UTIA (UTIAS) played in the direction that Bull’s life took. But thanks to Mrs. Alberta Patterson (more about her later), we have a copy of that Maclean’s article, so we can get the story of Bull’s rise right from the horse’s mouth so to speak.

Bull had what could be described as a Dickensian beginning. Born in 1928, Bull was 3 years old when his mother died giving birth to her tenth child. The Bull children were then cared for by their father’s sister, a retired nurse. But when Bull was 6, his father remarried, moved to Toronto and sent Bull and three of his brothers to live with their married sister. The summer Bull was 9, he visited the LaBrosses, his mother’s younger brother and his wife, on their farm near Kingston, ON. The LaBrosses had no children, and Bull was much happier on the farm, so he remained with the couple.

That winter, because the LaBrosses were headed to Florida, Bull’s uncle approached the Jesuit boys boarding school, Regiopolis College, hoping to find a place for Bull. Initially rejecting Bull for being too young, the headmaster reluctantly agreed that Bull could attend the school if he was picked up as soon as the LaBrosses returned. Two months later the LaBrosses arrived to collect Bull only to be told that Bull was an excellent student and the school wanted him to stay. Bull remained at the school until his graduation in 1944 at age 16.

Obsessed with airplanes, Bull had graduated in time for the inauguration of the University of Toronto’s undergrad program in aeronautical engineering. Again, Bull was considered too young for the program, but after being interviewed by the professor in charge, he was accepted. Four years later, Bull graduated at the age of 20, and his timing was perfect.

In 1948, with support from the Defense Research Board (DRB), Dr. G. N. Patterson was operating a new U of T supersonic lab located at Downsview. The lab was the first iteration of what would become UTIA, and then UTIAS. Not much teaching was happening in this newer area of research and only 4 students were going to be accepted that year. In what had become a theme in Bull’s life, the selection committee rejected Bull as being too young for graduate work. However, Prof. G. N. Patterson had taught Bull in the undergrad program and thought Bull “had rare qualities”, so Patterson accepted Bull as his graduate student: “I’ve had more brilliant students academically, but [Bull] had shown tremendous energy. As I was to discover later, sometimes not too happily, he had terrific ability to stick with a tough job and get things done, no matter what the obstacles.” This stick-to-itiveness was another theme in Bull’s life, and one that would ultimately lead to his downfall.

Bull not only became known for his ability to work tirelessly on projects, he also became known for being a creative problem-solver. Bull and his fellow grad student partner, Doug Henshaw, were tasked with designing and building UTIA’s first small supersonic wind tunnel. Prof. Patterson, their supervisor, whose office was next door to the lab, arrived one morning to discover that his office had been rearranged to make room for the wind-tunnel valve that was protruding into his office through a hole in his partition – the creative solution Bull came up with when he and Henshaw discovered at 1:00 a.m. that the wind tunnel was too long to be contained in the lab.

The next rearrangement of Patterson’s office occurred when Bull and Henshaw were building a larger wind tunnel. This time, when Patterson arrived at work, the partition was gone, and he had to climb over the top of the wind tunnel to reach his desk. Frequently, Bull and Henshaw would work perched on the edge of Patterson’s desk: “periodically, as Patterson tried to concentrate on desk work, he was almost lifted from his chair by the ear-rending screech of a blast of air shooting at two or three times the speed of sound through the wind tunnel four or five feet away.”

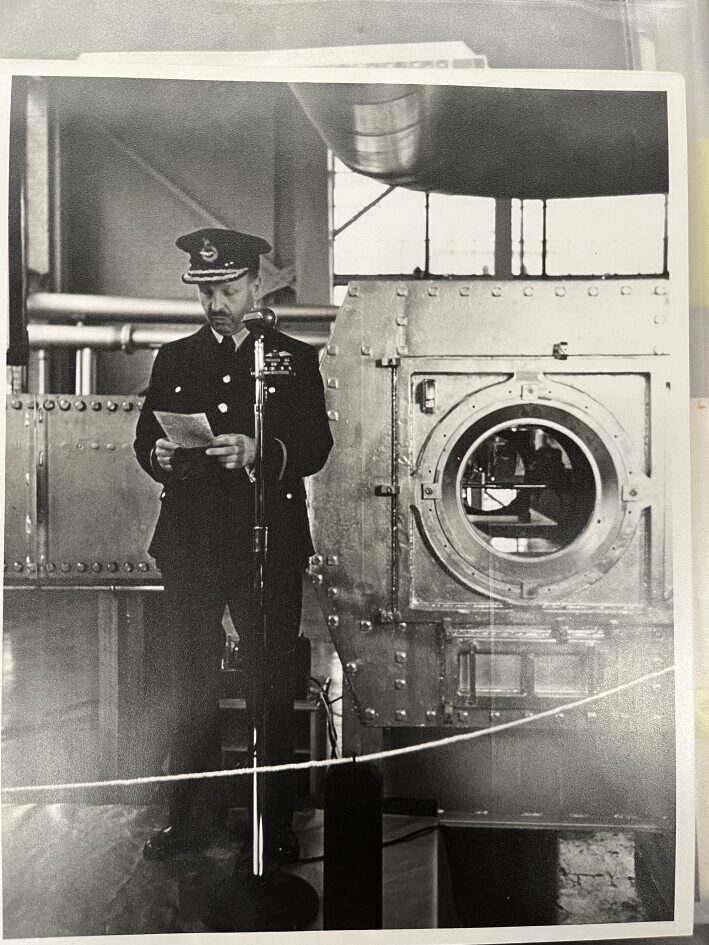

The final straw for Patterson came when Bull and Henshaw achieved three times the speed of sound causing the large observation windows on the side of the wind tunnel to explode and shower Patterson’s office with shards of glass. This led Patterson to ramp up his fight for more space. And, as discussed in our last email, Patterson not only obtained more space, he also received funds to refit the building for the creation of the new UTIA and to build the 40-foot wind tunnel sphere.

When work began on the sphere in 1949, Bull, age 21, was tasked with the “design and perfection of the test section of the wind tunnel –the critical ‘nozzle’ section where the highest air velocity had to be produced and where the actual testing of models was to take place.”

Fast forward a year and a half to fall 1950, just days away from the grand opening of the new Institute of Aerophysics (UTIA). As we know, critical to the opening ceremony (besides grand sandwiches) was a demonstration of Canada’s greatest new supersonic wind tunnel. Patterson, Bull and their group were hard at work assembling the tunnel and all appeared to be going well, but during the final test on the day before the opening, the wind tunnel did not produce a shock wave – yikes! To their horror, the team discovered that the tunnel was leaking and would need to be repacked, which was no small feat because it meant the removal and replacement of approximately 400 nuts and bolts. The team rolled up their sleeves and by 11:00 p.m. they were confident that all was back in working order, so Patterson et al went home leaving Bull with two machinists to perform a final test.

“... about 1:00 a.m., Jerry pushed the button...the whine of air inside rose to an ear-splitting shriek. A clearly discernible shock wave formed. The wind tunnel was functioning perfectly, pulling the air through it at a speed well in excess of the velocity of sound. Jerry and the machinists gleefully started pounding each other on the back. But it was all over in a few seconds. There was an explosive crash, a couple of echoing thuds, the wind tunnel shook, and the whine of air rushing through it suddenly became silent. Bull knew what had happened. Inside were two ten-foot-long blocks of wood which gave the tunnel its interior contour. The desired hardwood hadn’t been available in time and they had to use softwood. Jerry knew... the intense suction of supersonic-flowing air had pulled the heads of the bolts through the wood and the blocks had ripped loose and shot like artillery shells against the vacuum sphere end of the tunnel.”

There was no getting around it, the 400 nuts and bolts would have to be removed and replaced to repair the wind tunnel so that it would be ready for the opening demonstration a mere 12 hours in the offing. Bull was aware that all the hoopla around the opening was about the new supersonic wind tunnel, so he and the 2 machinists got to work. Little did they know that help from a very surprising source was on the way.

“Dean Kenneth F. Tupper...was driving home late, saw the lights of the institute still on, and dropped in... The dean threw off his coat, put on a smock and dug in. When someone had to crawl into the tunnel to loosen bolts from the inside, Tupper insisted on doing it himself.” With the dean’s help, the job was completed by 3:30 a.m. The dean then took them all out for breakfast before they headed home to get some much needed sleep. Bull himself said they would never have finished the job on time had it not been for the surprise middle of the night visit from Dean Tupper.

In 1951 when Bull was in the final stages of completing his PhD, Patterson, “so widely recognized as a guided-missile authority that he had been appointed chairman of a U.S. Navy guided-missile consultant panel”, was asked to recommend an aerodynamicist experienced in supersonics to help with the DRB’s project to produce a guided missile for industry production. You guessed it, Patterson recommended Bull. True to one of the themes of his life, Bull was considered too young for a job in which he would ultimately be supervising scientists older than he was. But, after his interview, Bull got the job and was launched into the world of top secret work.

Bull, of course, grew out of the theme of being too young and he rose to become internationally recognized as one of the world’s leading ballistics experts. In fact, his work on ballistics was considered so valuable, he was made a US citizen by a special act of congress in 1973. However, his stick-to-itiveness turned into an obsession and the intervening years between his graduation from UTIA(S) and his assassination read like a novel. No doubt Gerald Bull is the most notorious UTIAS grad, and he helped to create what became one of the most iconic structures at UTIAS – the 40 foot sphere. Bull was brilliant, and by all accounts, he was a very likeable guy. Dr. I.I. Glass, a research scientist at UTIA ten years Bull’s senior, said about Bull, “He’s the easiest guy to get along with that I know. He gets you embroiled in terrific arguments sometimes, but just when you’re starting to get mad he winds it up somehow so that you go away liking him more than ever.” Apparently, Bull’s likeability remained a constant and hundreds of people travelled from all over the world to attend his funeral. To find out about Bull’s career and what led to his assassination, I highly recommend PBS Frontline’s documentary at this link: | |

|